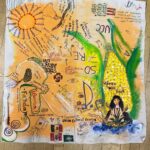

Gemaly Padua Uscanga’s visit left us with a song that tasted like a décima in our mouths, a purr of a tarima in our bodies, a mountain of memories full of children’s smiles playing around the tarima, and delicious smells of freshly made food that we cooked together. Our hearts were softened by the sound of the sones while rising through the air were the aromas of soup, pozole and tamales.

Her visit left us with the certainty that we are building a community with the technology the fandango tradition offers us; that we are creating a parallel territory, where all of us who want to connect with the ancestral wisdom that is preserved in this tradition, can have a space to fill ourselves with knowledge. A space where there is no exclusion, but instead a call toward reflection and commitment to protect this knowledge, using the value of the collective, love, and both individual and collective responsibility as guides for the construction of that territory.

Seattle Fandango Project is a collective that has existed for many years, before MÁS was born as an organization, and serves as a collective of stewards responsible for continuing the tradition of Fandango here in Seattle. It has been an honor for us to collaborate on this occasion with the Seattle Fandango Project, to make possible this gift that life has given us of hosting a woman with so much love and power to share and teach. Gema’s visit reaffirmed the community ties that MÁS and SFP have been building and invited us to affirm again that collaboration is the way and that together we are stronger, that we must continue to foster together the reaffirmation of this territory of knowledge in migration and affirm that art is political; that these traditions are linked to the struggles and resistance of the territories from which they originate. We invite ourselves to approach and understand the struggles that we face in this territory where Fandango lives on – not as an art to be consumed – and to continue the path of organizing with and against those struggles.

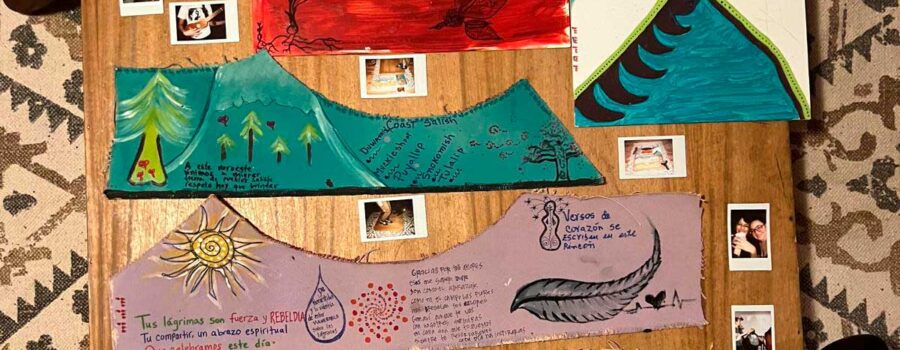

Collective Reflections from the Seattle Fandango Project

-

- Affirming the connection and affirming the technologies in our territories. Being.

- Gema leaves us with an energy of union, connection, and encourages us to continue growing.

- The honesty Gema shares invites us to be ourselves and to be honest

- Her visit gave us the opportunity to connect with Fandangueros from Vancouver.

- Gema has the power to encourage us to open up and be sincere and that is very special.

- The way Gema shares and the fact that tears come and she continues sharing is part of being and there is no need to ask for forgiveness, it is part of a process and that teaches a lot and opens up a possibility to connect in a way that sets the tone for connecting at the level of the heart and with vulnerability.

Gema is a ruminant of thought

Verses:

ruminant of thought

I came to Seattle

My song is a walk

With tears of feeling.

Gema, as she is called by those closest to her, is a guardian of the traditional music of her region; Jarana or “Son Jarocho”, fandango music, she is an interpreter of the guitarra grande (big guitar) one of the most representative instruments of the community of Chacalapa, an instrument that performs the functions of both bass and percussion. Student, community health worker, and the most demanding task, mother of a teenager. A constant learner of life, people, and art. Founding member of the Altepe Collective.

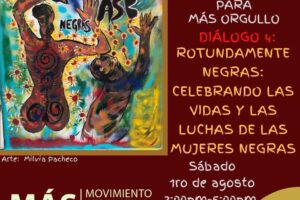

The following are the highlights of the conversation between Milvia Berenice Pacheco Salvatierra and Gemaly Padua Uscanga:

Tell us, how did the Altepe Collective come about and what does it do?

It is a multidisciplinary grassroots organization that is 18 years old. It started because of our love for music, the fandango, since most of the members met and got to know each other in that space, in the popular festival of our region, and after the music, it was like that opened a bridge for us. Also, some of our comrades had come from community processes such as radio, video, so we started gathering that knowledge we had been learning to share it with our people, with our communities, because the collective is made up of young and not so young people from different communities and from the south as well.

And now our work is more focused on political training, as educational work, with youth and children of the region, in the defense of the territory and in the care of life.

Keep listening to the conversation between Milvia Berenice Pacheco Salvatierra and Gemaly Padua Uscanga for this Afro Saberes.

That makes me think of one of the spaces where you have been sharing that wisdom, we were wondering how to emphasize this idea that culture is political, and that through the work you do with the Altepe Collective with the communities, you use the fandango as a tool to talk about the realities that affect the communities and also as a way of doing, claiming, resisting and celebrating what is done. Tell us more about this.

I think the fandango has been a way in which we have built our way of life, a way to organize ourselves that has to do with many other things. Generally when we talk about the fandango, we think of it as the central axis of our community organization, but in reality I think we have been doing a work of internal reflection, understanding that the fandango is part of the territory and not the other way around, right? Instead it is the territory that shapes the community and all these things evolve from there, and we as part of the community, we form these assemblies, we form the party, we form the organization and so on, and that’s been something that we’ve learned with the older people.

Yes, it is in the music, in the fandango, but also understanding it as that, as a dignified way of life and other tools that are a fundamental part of the work that I could identify in four moments; music, art, communication, defense of the territory. And this work of human and cultural rights, working with other organizations, because our work has somehow been self-managed, it has been sustained because work has been done as collaborative networks at a local level, but also at other levels, right? Local, regional, in our state, but also in the country. And also, these connections have made it possible for one to be here

Sharing what sustains the work, well, it involves art, it involves music, to learn these radio tools, to keep ourselves updated as technology advances and not merely going with the rhythm, but doing it according to the rhythms set by our way of life, not according to how we decide to carry out our work and that it’s also seen as a playful tool for young people, not this recording ourselves as something that attracts attention, because now many generations are born were born with this possibility of having access to the internet, access to certain devices that other generations did not, it turns out that it was more difficult, but now we can use these tools that for many are very easy to have, but also make them easily available to others. So making videos, creating radio broadcasts has also been a process of documenting our reality and talking about our own aesthetics, that we see ourselves reflected in that reality and not necessarily that we have to look for a reality that does not belong to us from the hegemonic media, from this massiveness that then overtakes us as well.

What are your reflections in relation to what is involved, what it means to preserve these traditions? To take the fandango tradition out of the territory and to connect with people who are doing the same thing from other latitudes.

First of all, I am very happy and also grateful, because ultimately it’s the result of these relationships that continue to be fertilized and built. Meeting in person is always very emotional, comforting and hopeful, because we talk and share, as you say, from the virtual space, but then it seems like something that cannot materialize because it’s 2021 to 2024, that’s three short years.

It is not the same as talking about them, planning them, thinking about the meaning they might have, how to reach these communities, these spaces, it feels like a dream materialized and that is something very cool, very beautiful because it has been like the one that was being built alongside other processes that in some way, with the Altepe collective, some of us already knew or placed certain people. But now it is once again reconnecting and well, this is the third time I’ve come to the city, and it was the opportunity to connect with people in San Diego, in Tijuana, in San Jose, in Watsonville, and from there to come to Portland, to greet friends in Salem and to come here and also meet the colleagues of the Fandango Project, and now to connect directly with MÁS and with everything that is being built. I think it is also a way of recognizing the work that is behind so many people so that we can get together, so that we can see each other, so that we can catch up, but also to see what other things we can do to reinforce and strengthen the work or the things that we are doing in our territory.

Regardless of these distances or these borders that can be like that limiting factor if we think of them as that, but just by dialoguing, sharing, then that thing is the least of it, that becomes like an invisible thing, as if it does not exist. And it’s also recognizing the processes that we had in order to reconnect, that maybe we are in other stages in our jobs, in our work, but if right now we’re in that like reconnection, it’s also like giving each other a hug, but it’s also like shaking hands, seeing how we support each other and I think that music becomes like that bridge, but also like the people that make it possible for this to be felt.

We are also kind of dividing, because the first time we came here was 12 years ago. So it’s afterwards, it was like seven, eight years ago and now I don’t come with the collective, but I know that there is work being done with all the comrades who are part of the collective, who are sustaining it. Well, also like my stay in these places to be able to share what is being done there and I say no, Gema’s not doing it, Luz is doing it, Sael is doing it, Chirro is doing it, Emiliano is doing it, Cindy, Miguel and Dani are doing it, a lot of people that I’m not going to mention by name because later they are going to say you did not name me, but well, it’s that.

How to recognize the work and the fruits of the care and the fertilizer we apply to our relationships.

Culture is political, because we also do the work of making sure that what we create responds to the needs we have in our places and so it breaks with many schemes that are supposed to be done in a certain way.

I think I have already said it, but what has resonated with me, is to recognize that we are in another moment, in our processes and to see how we were thinking about these things, we tried, we didn’t try, it worked, it didn’t work, what worked has now served us for this other thing. I don’t know, now, sharing this thing that has happened with the music, not necessarily only jarana music, fandango music, but these creations that the girls, the boys in Veracruz are making and sharing them here. Well, as I was saying, I listen to them every time I share them, and likewise it makes my chest swell.

In this artistic and cultural journey with MÁS, what other things, other elements have you perceived as common elements in these different manifestations?

Well, I think something like that. Because that, that is not done, a person does not do it alone, and I think that’s important because sometimes, I don’t know if it’s unconsciously or consciously, that is also kind of part of the reflection that we then separate everything, because it’s easier, because it’s more comfortable, because it’s more adaptable. If you take one thing out of something so broad and so deep and so deep-rooted, well, it’s incomplete, and if it’s incomplete, then obviously there’s going to be something unsaid, something that doesn’t come together, right?

So, I think in bomba, capoeira, taika, and obon, none of those those expressions, at least the ones that the people…Atajo de Negritos (an Afroperuvian tradition), obviously, if one or two people came to share that expression, the reality that was always present is that it wasn’t an individual thing, that everything was done in community and that all of that was done exactly like that, collectively and each element, in doing it, has a significance.

I love bomba and now I understand it from a different perspective. And that seemed very cool to me, because we always talk about how it imposes on us, right? We’re afraid to enter the batey, but they also said, we’re also afraid to enter the stage. That ‘s how this is a challenge, to enter and participate in La Rueda is something else, isn’t it? But then when we began to share the other ways, we have that fear and we talked about it and it also has to do with all that memory that we keep in our body, that sometimes is not even ours, but that we have it there, crossed by our own ancestors and we want to see it in that way, but it manifests itself in our body and then it comes out as a little “stop”, but there is another part of us, that is like that need to be part of that feeling oneself, to let the body move, to let it bring out whatever it wants to bring out, and for example with Taiko I felt it was very similar to capoeira. At some point in Sembradores, which was one of the spaces we held with the Altepe Collective in Acayucan, which was one of our like houses, we practiced capoeira there, and sometimes there happened to be a certain tension between some of us who were participating and unintentionally, sometimes we had to play the game in La Rueda with that person with whom we had some little thing and then I had to figure out how to remember that it wasn’t a personal thing that we were sharing and we’re there learning too.

And since art is an element that transforms the pain and the experiences of violence that these communities go through and that they continue betting on life and that they continue betting on looking at the world from the point of view of surrender, from the point of view of saying:

I am here to protect, I am here to deliver, I am here to sign life, not to control it, not to eh, produce it, not to grab it, not to take it away, not to extract it, but I am here in spite of these difficulties to generate life and I continue in spite. Pain generated life from this pain to transform it and to affirm who I am. That is very powerful.